By Wissam al-Saliby

November 7, 2024

Upon starting work in the field of Christian religious freedom and human rights advocacy in 2018, I noticed that national and international Christian institutions, denominations, and alliances frequently had separate commissions or departments focused on advocacy and peacemaking, respectively. Over time, I’ve found that this distinction between peacemaking and advocacy is counterproductive and has negative practical implications for our work. Let me explain why.

Initially, I accepted this division as natural and obvious. After all, peacemaking and advocacy are two distinct disciplines. Advocacy requires an advanced understanding of human rights law and humanitarian law. The concept of human rights is a secular interpretation of the biblical notion of the imago Dei. I pursued human rights advocacy at the United Nations while working at the Geneva office of the World Evangelical Alliance.

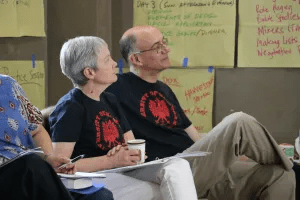

Dan and Sharon Buttry (Credit: Globalpeacewarriors.org)

On the other hand, peacemaking is relational and experiential. The concept of reconciliation is profoundly theological and rooted in God’s mission of reconciling humanity with Himself. In the early 2000s, I learned about peacemaking through working with colleagues in Lebanon. Although they were working from a secular orientation, they shared with me that the modern discipline of peacemaking had been developed by Mennonites, Quakers, and Brethren churches and universities. Later, I met Dan and Sharon Buttry who raised a generation of peacemakers worldwide while working with International Ministries of the American Baptist Churches.

However, as my religious freedom advocacy work progressed in Africa, Asia, and the Middle East, I saw that the division of labor between peacemakers and advocates led to wasted resources, overlapping programs, and missed opportunities. The same evangelical organization would often have two separate teams in a country: peacemakers and advocates. That was the case even though both efforts have much the same goal: to ensure that evangelical Christians and churches can fulfill God’s calling and that all citizens’ rights and dignity are respected, regardless of who’s a minority and who’s a majority.

In countries where religious freedom is threatened by social hostility rather than government restrictions, we need to equip pastors to be peacemaking to advance religious freedom. According to PEW research, among the 25 most populous countries, Nigeria, India, Egypt, Pakistan, and Bangladesh had the highest levels of social hostilities relating to religion. When violence impacts religious groups in these countries, we need to seek justice for the victims and hold perpetrators to account, and we also need to plant the seeds of reconciliation and avert a future round of violence.

21Wilberforce’s team recently spoke with leaders in a country where churches had been ravaged by large-scale mob violence. We opened our hearts and ears and prayerfully considered how to partner with those suffering persecution and align ourselves with their calling. We are currently supporting the churches there on a range of issues, including psychosocial support for those affected by violence, equipping pastors and community leaders with peacemaking tools, and advocating for justice and against impunity.

The strategizing, planning, and implementation of peacemaking and justice advocacy programs cannot be done separately. Our Christian institutions need to reconsider the peacemaking-advocacy institutional dichotomy so that our public engagement is more coherent and strategic.

Peacemaking primarily, but not solely, prevents religious freedom violations through building community cohesion and peaceful societies. Advocacy mainly, but not solely, seeks justice and redress for religious freedom violations. Peacebuilding and advocacy fall on a spectrum. There they are complementary, sometimes intertwined disciplines. After all, there can be no true peace without justice.

Featured image caption: According to PEW research, Nigeria is among the 25 most populous countries with the highest levels of social hostilities relating to religion.