October 28, 2024

By Trent Martin, 21Wilberforce Advocacy and Training Coordinator

As 5,400 people raised their voices together on the opening night of worship, I was swept up in the truly global picture of the body of Christ. It was the start of the 4th Lausanne Congress in Incheon, Korea, a continuation of a movement started in 1974 with an international gathering of evangelical leaders in Lausanne, Switzerland. That first gathering produced one of the most influential documents of the modern evangelical movement that provided a strategic vision to work together as a united Church to reach unreached people groups and fulfill the Great Commission.

This fourth congress continued to build collaboratively on the themes laid out in the first and subsequent gatherings, bringing together Christians from around the world to spark ideas about addressing the “gaps” that Christians need to fill as belivers seek to share the good news about Christ to the end of the earth.

Religious freedom was one of the key topics at the Fourth Lausanne Conference. In his introductory remarks to launch the Congress, Michael Oh, CEO of the Lausanne Movement, shared that “the most dangerous words in the global church today are ‘I don’t need you.’”

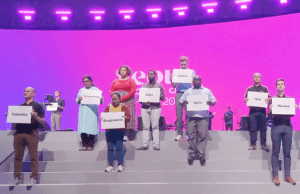

Representatives of national churches on stage with the names of their countries to call for religious freedom. (Photo: screenshot of the 4th Lausanne Conference livestream)

This set the stage for a week full of collaborative sessions centered on building connections and discussing solutions among a diverse group of Christians to bridge the “gaps” in how the Church approaches its mission.One of the 25 primary gaps identified was the need to develop “Christians in the church, parachurch, and workplace” as peacemakers who can address the rising challenges of religious persecution.

Citing statistics from the Pew Research Center, Lausanne’s State of the Great Commission Report highlighted that rising state restrictions on religious freedom around the world are challenging the core Christian tenet that people made in the image of God need to be treated with dignity. According to Open Doors, Christians face the highest overall persecution in North Korea. The country with the highest levels of violence against Christians is Nigeria. The rampant militant and extremist attacks in the country resulted in over 4,000 deaths in Nigeria, representing 82% of the total number of Christians killed during Open Door’s reporting period.

The Book of Acts provided the focal point of the Bible studies throughout the week. I saw that despite, and sometimes because of, the persecution the early church faced, the church remained faithful and grew exponentially. The continuing faithfulness of Christ to his Church was on full display in the encouraging stories from our brothers and sisters who shared their stories of perseverance through persecution at the Congress. Nigerian leaders shared how they cared for their neighbors facing the destruction of their communities to violence, Asian leaders celebrated how their churches sent thousands to share the good news of the gospel with the unreached, and the Middle Eastern believers who faced imprisonment for their faith remained joyful in their calling.

However, the conversations I had with leaders who are facing these realities revealed that there is much work to be done to equip the church to face these challenges with wisdom and the right resources.

I discussed with one leader from South Asia how he was building resources and training for Christian leaders in his context. He shared that many pastors would launch into outreach ministry in their community with the best of intentions, but their lack of preparedness and overly public approach invited a backlash of arrests and violence against the church for violations of anti-conversion laws. While some of the persecution against Christians may be inevitable, he sought to equip leaders with the tools they needed to know how they could shape their church outreach in a way that accounts for the legal, cultural, and political context of their community. If there is an arrest of a Christian, they want to utilize a network of trained local Christians that could quickly intervene with the local police to try to get the person released before they enter into the legal system.

These conversations fit into the broader talks shared from the Congress plenary stage, where speakers discussed how fulfilling the goal of sharing the Gospel to the ends of the earth needs to be done in a Biblically wholistic way that mobilizes the church to care for those who face injustice and takes account of the local context where the ministry is taking place. Throughout Scripture, it is clear that justice for the oppressed is at the core of God’s heart for the world. To work most effectively on the Great Commission, churches must be equipped to prepare and respond to persecution and other forms of injustice.

One of the Lausanne coordinators of the religious freedom gap focus group stated that “advocacy for the persecuted doesn’t work if you don’t learn to work with people of other faiths.” She shared how oppressive governments often use the strategy of stoking divisions between marginalized communities to keep them isolated and unable to form a united front to advocate for their rights. Unfortunately, our church leaders can support that strategy when we say “I don’t need you” by our words or actions to people of other Christian traditions or those of other beliefs. In the focus group, we also discussed how if we truly believe that every person is “made in the image of God,” we should be willing to defend their dignity and show Christ’s love to them, whatever their beliefs.

Another theme that ran throughout the week was the global reality of “polycentric Christianity.”

The highest population of Christians is now in Africa, with Latin America and then Europe coming in second and third. The growth of the Christian population in Africa is projected to continue strongly as “more than half of global population growth between now and 2050 is expected to occur in Africa.” As the global Church grows in Africa and Asia, it is growing on the continents where Christians are facing the most severe levels of persecution. As Christian population centers shift, it is time to build centers to equip the church to respond to rising persecution. Organizations that seek to advance religious freedom and support the persecuted church from outside the African and Asian context often keep the locus of their resources and personnel in America and Europe. While this has helped empower a global movement of governments to support religious freedom, as shown by institutions like the International Religious Freedom or Belief Alliance, it has failed to substantially reverse the rise of persecution. Part of the reason is likely the lack of engagement of key countries in Asia and Africa. Of the 38 countries that have joined the Alliance, there are 6 African countries (Cameroon, The DRC, The Gambia, Senegal, Sierra Leone, and Togo) and 3 Asian countries (Armenia, Georgia, and Israel) that have joined. While the lack of some key players in Africa is apparent, the gap in Asia is especially glaring. Even the key Asian democracies of Japan and South Korea have only committed to being “friends” of the alliance without agreeing to full membership.

True change in the countries that face persecution is not likely to happen simply due to outside censure or sanctions that have limited or even negative effects that can play into narratives that present Christianity and religious freedom as tools of a “Western” agenda. If the church and religious freedom advocates want to see long-term change, we must work with all our partners in the reality of a polycentric world to develop a clear strategy for empowering dynamic local, national, and regional networks to stand for religious freedom. While the value of religious freedom is universal, the institutions and means of implementing that freedom must be locally shaped and grown.

I ended the jam-packed week with a trip just 30 miles north of the capital city of Seoul to the demilitarized zone (DMZ) between North and South Korea.

North Korea

After passing through the military checkpoints, where the guards looked over the passports of our Congress group, we parked the bus and walked into the Aegeibong Peace Ecological Park. The park is built on top of a 154-meter rise called Aegibong Peak, which overlooks a sweeping vista of both North and South Korea divided by the Jogang River. On that clear, sunny day, I could see half a dozen farmers baling hay and several villages as I looked over the river into the farmland from the observation point. A river was the only major physical barrier, but a much wider gulf divides the North and South. While South Korea is the country that sends the 3rd most Christian missionaries in the world, the Communist regime in the North makes it impossible for the estimated 400,000 remaining Christians in the country to freely live out their faith. North Korean believers face death or imprisonment in the regime’s brutal forced labor camps if their Christian identities are discovered.

One of the Korean pastors in our group shared with us how his family was divided during the Korean War. His parents fled their home in the North but left his older brother in a safe location where they planned to return after the conflict. The ceasefire agreement in 1953 created the 4,000-meter DMZ and prevented either side from crossing this zone. It also solidified the division of thousands of families, like this pastor’s, with relatives often never knowing where their loved ones were or if they were even still alive. The pastor’s parents wrote on their tombstone, “You will always be remembered,” hoping that one day their lost son would be able to see that they had never forgotten him. The pastor is part of a community that prays and works for the possibility of reunification and ways to share the hope of Christ with those in North Korea.

The faith I saw in that Korean pastor and the many other Congress leaders tackling persecution in their countries I talked with that week sparked hope that we can mobilize the global church to stand with and empower those who face persecution. We must remember their challenges and mobilize local centers of advocacy that can turn the tide on injustice.